The Global COE Program on sustainable humanosphere began in July 2007, with the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) involved as a collaborating institution. To engage in the interdisciplinary study of sustainable development in Asia and Africa from a global and long-term perspective, this program has mobilized area studies specialists from four institutions: CSEAS, the Graduate School of Asian and African Studies (ASAFAS), the Center for Integrated Area Studies, and the Center for African Area Studies as well as scientists working on frontier technology at other institutes and schools, including the Research Institute of Sustainable Humanosphere. Scholars at the Institute of Sustainable Science, the Institute for Research in Humanities, the Graduate School of Agriculture, and the Graduate School of Engineering have also been participating in the program.

Our main aim is to create a new paradigm that calls for a fundamental shift in the values and norms underlying our understanding of the environment and sustainability. As a result of being ranked highest in the intermediate review conducted last year by a panel at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS; our sponsor), our enthusiasm and confidence has increased further. As we enter our fourth year, I see no danger of this group losing its intellectual energy. We are also confident that the present level of funding will continue until the program is completed.

For the past three years, we have pursued the twin aims of paradigm formulation and graduate and postgraduate education. Responding to the launch of this program, a new division, “Global Area Studies,” was created at ASAFAS. Several postgraduate students enrolled in the degree course on sustainable humanosphere in this division are currently working on doctoral theses related to the paradigm. Many others are engaged in fieldwork with the financial assistance of this program. Meanwhile, it was always those postdoctoral assistant professors and researchers who are employed by this program that had driven our intellectual endeavour, paradigm formulation, by linking research to education programs. They share a work space, and their daily conversation has been a major source of inspiration, which informed has the staff, myself as convener included, of new research agenda. In addition, a series of research meetings among all members committed to the program has been held to ensure full communication among researchers from diverse disciplines. The first result of this effort emerged in March 2010 under the title In Search of Sustainable Humanosphere: A New Paradigm for Humanity, Biosphere and Geosphere (Kyoto University Press).

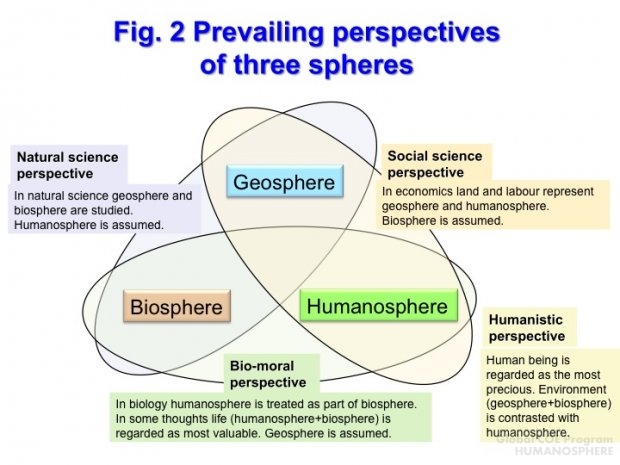

It is envisaged that in two years’ time the full outcome of our research will be published. Six volumes may be necessary to adequately cover the range of our studies. The publication of two edited volumes in English is also planned. In these publications, the basic tenet of the paradigm formulation will not change. The Introductory Chapter of the aforementioned book set out three types of paradigm shifts in terms of the range of enquiry: 1) from “land surface” to the “humanosphere,” a three-dimensional environment focusing on the movement of water, air, and material and energy conversion; 2) from “production” to the entire process of “human life,” including the intimate sphere and life cycle; and 3) from “temperate zones” to the “tropics” as the geospheric and biospheric centre of the earth. The definition and contents of such key terms as humanosphere, human life, and the tropics are yet to be fleshed out and fully developed.

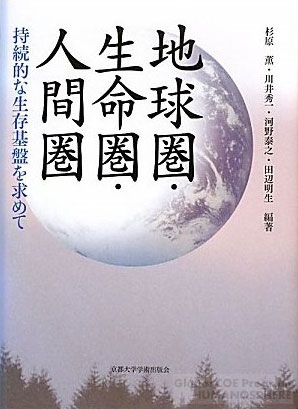

I would like to devote the rest of this essay to introducing some of the more recent discussions we have been having in an attempt to create the “humanosphere index.” Figure 1 shows the parallel evolution of the three spheres, which comprise the humanosphere (in the broad, real sense), and their interactions. It is well known that the “human development index” concentrates on the indicators related to the sphere of human activities such as per capita income, health, and education, which may be called the “humanosphere” in the narrow sense. From our perspective, however, the human development index covers just one-third of the real humanosphere. Our index integrates indicators related to human interactions with other spheres, such as human capacity to deal with geospheric disasters and efforts to conserve biodiversity so as to enable it to better represent the “basis” for and “purpose” of people’s livelihood in local societies of Asia and Africa.

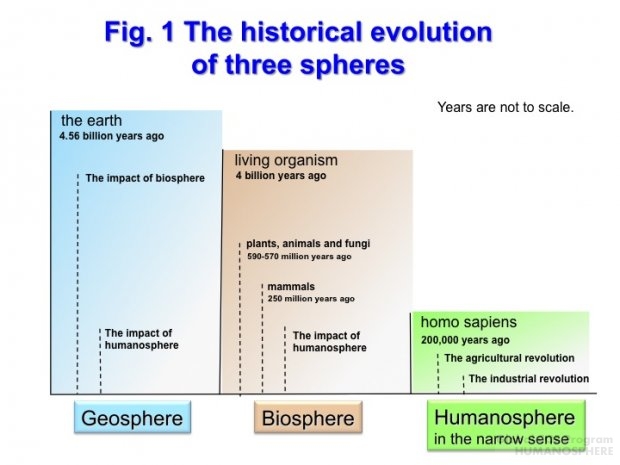

Figure 2 shows the scope of enquiry of prevailing disciplines and thoughts regarding the humanosphere. While we readily accept that humans need to prioritize themselves in times of emergency and for survival, so that we do overlap with the humanistic perspective, we clearly diverge from some aspects of modern thought (such as the full liberation of the human desire to consume or the unlimited exploitation of natural resources) by committing to the sustainability of the geosphere and the conservation of the biosphere. In this context, we acknowledge the sustainability of water, air, and soil, as well as the entire process of material and energy circulation as the basis for human existence. We also propose a much fuller recognition of the intimate connections between humans and other forms of life, to the extent that the former cannot exist without the latter, and vice versa.

Figure 3 was drawn to emphasize the breadth of climatic diversity in the tropical and semitropical zones, ranging from tropical rainforest areas to the desert. This diversity is arguably one reason why modern technology and institutions developed in temperate zones have not been immediately useful in the tropics. Thus, if we wish to think about the sustainability of the earth as a whole, the future direction of technology and institutions must take into account the ecological and climatic diversities of the tropics (and, by extension, of all aspects of the global environment, including the frigid zones).

Such thinking has already enriched our discussions on “livelihood.” For example, one study of an African society in which there was a high prevalence of the HIV virus proposed that the livelihood of the people there was seen as it was, taking the occurrence of the disease for granted at least in the short to medium term. Here, the sustainability of livelihood requires not only controlling the environment, but also living with it and at times becoming part of it. We need to develop these ideas further, through close observation of the tropical humanosphere and through conceptualizing the values essential for human existence.

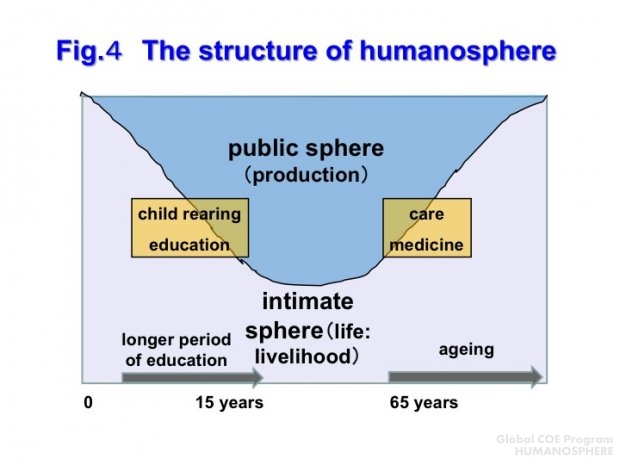

Lastly, I would like to present Figure 4, which is still in the making. This is an early version; different versions have been suggested by members of the group. Values such as affection, acknowledgment, and dignity are usually considered to belong to the “intimate sphere” and are regarded as more “subjective” than values advocated in the public sphere such as freedom, equality, and work ethic. However, humans usually begin and end their lives in the intimate sphere and feeling affection or the recognition of dignity often becomes crucial at such moments. These values do not disappear when humans are active in the public sphere. As the period of education becomes longer and life expectancy increases, the time that humans spend in the intimate sphere is unlikely to grow shorter relative to that spent in the public sphere. Furthermore, those areas in society where a close collaboration between the intimate sphere and the public sphere is required, such as that between childrearing and education or that between medicine and care, have become important for sustaining the livelihood of the people. Indeed, a society that does not have a firm basis in the intimate sphere may not be able to secure a workforce of good quality, which is essential for production and other economic activities. This indicates the fundamental importance of the values of the intimate sphere in the working of the public sphere, and for the quality of humanity in general.

It is thus evident that our efforts to understand the sustainability of local society in the tropics have direct implications for the understanding of contemporary Japanese society. This also serves to inspire and motivate us.